Uncategorized

A Brief History Of Carpets

Various sources, carpet constituting the original word Kali ‘s (decrease should shape permanently ) from the Persian also been claimed came James W. Redhouse in 1890 gave the Turkish word in the dictionary published ( in Turkish and İngilizce Lexicon , p. 825), F. Steingasse two years later, he removes the Persian Dictionary in both Kali ‘s , both in this language carries the same meaning as her thick in (a precious carpet varieties, mats, rugs) stated that Turkish ( Dictionary , p. 949; thick / Kalıñ means “the weight given to the girl’s side before marriage” in Turkish [ Clauson , p. 622, 707]). Doerfer , on the other hand, makes use of many sources and proves that these two words were transferred from Turkish to Persian ( TMEN , III, 396-398, 399-400). In Turkish , there is also a word keviz / kiyiz / kidiz expressing mats such as carpet, rug and felt ( Clauson , p. 692, 707). The abundance of terms related to carpet weaving in Old Turkish is striking, and this shows the level of Turks in carpet art.

It is seen that the carpet is mentioned in various parts of the Old Testament . After counting the weaving materials such as the white fleece from Damascus and Helbon and the yarn from Vedan and Yavan in Ezekiel’s elbow for Sur, it is said that “ Dedan was yours for riding horses ” ( Ezekiel , 27 / 18-20). It is accepted that the word fabric is used instead of carpet because the cover placed under or on the saddle is a mat like felt, carpet, and rug rather than fabric. It is understood from the sentence “I spread carpets and variegated covers made of Egyptian yarn on my bed” (7/16) in the Proverbs of Solomon . II. In Samuel, Hz. Among the gifts brought to Dawud , the ” saffot ” was interpreted as a carpet (17/18). The words “O those who sit on carpets” in Judges (5/10) and mention of carpets laid for the guest to sit in Isaiah (21/5) show that the Israelites knew the carpet. However, it is difficult to say that the carpets they used were made with the knot technique. However, the depiction of the loom in Ancient Egyptian art ( DB , V / 2, p. 1995) bears a great resemblance to the looms still seen in Central Asia . This loom resembles the type of loom called “konar nomad” in Turkish , which is set up parallel to the ground and is mostly used in broadcloth weaving. In Konar nomads, arc ropes are wrapped in beams that are leaning or tied with ropes on piles driven into the corners of a rectangular area, and weavers work by sitting on the ropes or the woven part. Until recently, it is seen that Kyrgyz women weave carpets and rugs in this style ( Tzareva , p. 8-11). Homer ( BC IX. Century) mentions the carpet, VIII before AD. Depictions of carpets are seen on Assyrian frescoes from the 20th century; however, it is unclear whether they are of the knotted type.

In Arabic, mats, including mat, are called bisât in general . Navigated on a sightseeing earth Kur’an’da to bisat is compared ( Noah 71/19). During the Jahiliyya period, the Arabs knew him, although they did not have many carpets in their houses; Some words they used in exchange for carpets and rugs show this. One of these tınfis A / tunfus to d ; This name is given to thin pile or fringed mats. In the description haven in Kuran said zerâbî de (al Ghashiyya 88/16) is interpreted as a carpet ( zirbiyy A / zürbiyy A / zerbiyy in the plural; Ibn -threshold is ” ZRB ” Md. ). This name is given to the herbs forming a yellow, red and green color composition in autumn (Elmalılı, VIII, 5780). It is understood from the fact that Serir is mentioned together with the sofa and the pillow and the phrase “spread” is what is meant in the verse . The word is mentioned in a few places in the hadith. One of them concerns the return of zirbiyya taken from a woman belonging to Bani Anber after a seriyye ; A sword and some barley were given to its owner in return for this mat , which could not be returned because it was lost by the buyer ( Abu Dawud , ” Aḳżıye “, 21). Bukhari’s Hz. A rumor to Umar virtue said abkarî word zerâbî accepted and fine hairy or downy carpeting ( tenâfis ) are interpreted as ( ” Feżâ’il the ASHAB-Nabi “, 6; identical, XIII, 264-265). Ibn -threshold is, abkarîn the “embroidered silk mats” or “tightly woven carpets” As a variant the meanings indicates ( en Nihây to ” ‘abḳ is ” md. ). Arabs, then the carpet is often used as a prayer rug for Sajjad their moment by name.

The raw materials of the carpet are wool (sheep, camel), silk, cotton and mohair, and the knot threads are made of wool or silk (or a mixture of these two); others are mostly used in weft (warp) and weft (weft) threads. Since the quality depends on the raw material, long wools taken from the back of the animal are preferred for knot ropes in wool carpets. XIX in the dyeing of the ropes of great importance. Until the middle of the century, only natural dyes obtained from plants and insects were used. For example, blue, indigo and indigo; yellow, saffron flower and turmeric root; from the purple, prickly sea snail; red was also obtained from red beetle with madder. Since the 1860s, with the development of chemistry in the West, natural dyes were rapidly replaced by synthetic dyes, but the cheap dyes preferred due to their very expensive quality caused the colors and motifs to mix with each other during the washing of the carpets.

Small or narrow rugs are generally woven on small looms that are leaning against the wall and whose side trees are not fixed, and large-sized carpets are woven on large looms called isdar , with fixed side trees. There are two round posts that can rotate freely around its own axis at the top and bottom of the two side boards of the counter. These warp from the upper pole mast, the top beam or direz the called warp threads to the above, so-called lower pole or Levendi carpet and the carpet is wound thicker, which in the following. The weaving of the carpet on a loom, which has parts such as loom iron, tensioning vise, power stick, cross bar ( varangelen ) and iron rod that is used to wrap the lower beam as the carpet is woven, weaving the carpet respectively warp knitting, knitting of the head knitting, crossing the cross thread, attaching the warp to the loom, knitting the power, knitting the warps. It starts with stretching and knitting the fence. In the upper part, a rope stretched from one end of the side boards to the other end or a thin stick of colored knot rope balls are arranged in rows and the desired ropes are pulled according to the motif.

Carpet, wool or silk threads of different colors are knotted around one or two of the aris threads to form a pattern and cut with a knife and the weft threads passed over it are tightened with a comb called kirkit. It is created by clipping in height. Two different types of knots are applied during tapping: Gördes or Türk knot, sena (sine) or Acem knot. In the first type, the knot is thrown by pulling the yarn over two strands and pulling it through, giving a symmetrical appearance. In the second type, the knot is thrown by passing the yarn under one bee to the right or left and looping it into another; this type of image is asymmetrical. Since the Novice knot can be tied more frequently, it facilitates the processing of more elegant motifs; however, a stronger weaving is obtained with the Turkish knot. In order to make the carpet thin, aris and weft threads are made of cotton. In addition, young girls and children with little fingers are employed in the weaving business. In a third type, which is seen mostly in Egyptian and Andalusian carpets other than Turkish and Persian knot types, the knot is tied in a single warp thread.

The motifs of the carpets are removed from memory or from an example as a result of many repetitions; sometimes very small type rugs are copied from another carpet by counting the knots from behind. Also similar geometrical model acquired motifs for carpets ¼ proportionate to the exemplary woven carpet or also on several water formed as model, broad edge is located mid-sized core benefited from the carpet by sprinkling patterns. The most practical method in this regard is to draw the motif on a checkered paper. This paper is called “sample”, ” talim ” or “boss”. The bosses are prepared separately for the curb, corner, floor and core. During the implementation of the number of nodes to be equal and the same thickness of the rope motifs used a great importance exhibit . The high number of knots per 1 square centimeter indicates the quality of the carpet; this depends on the fineness and the number of argaç and weft threads, the type of knot and the type and density of the knot . If the arches are frequent and tense, the knots are less, the knot rope is thin and the loop is tight, the number of knots per square centimeter increases; For example, Hereke rugs have thirty-six knots in 1 square centimeter. The presence of a maximum of two rows of knots between two rows of knots, the tying of the knots properly and at right angles to the ribs, the short and the same level of the feathers, the harmony and harmony in the colors and motifs are other features that determine the quality.

In carpets and mostly floor carpets, the surface consists of three main parts: border, floor and corners. The place between the outer hard part and the detached frame separating the floor and the hard part, which is wrapped with white wool or colored cotton yarn called flesh or coastal ( overlock in machine carpets ), is called a border. The curb has a wide belt in the middle, with one, two or more water next to it. The part enclosed by the border is called the ground / middle and has two shapes, monotonous or concealed . Uniform floors are flat or usually consist of repeating the same motif. These types of floor rugs are known as red, speckled, and sprinkled speckled according to the dominant colors and motifs on the floor.

In addition to the delicacy and elegance in the painting of the motifs, it is seen that the types of the carpet are also important for the carpet to be valuable. Unlike Western carpets, nature is not imitated in the oriental rugs; symbolism is generally dominant in motifs. Pretextat Lecomte points out the differences in the pattern understanding of the West and the East, saying: “In Europe, bouquets of ideal flowers are drawn; but their silhouette is so realistic that the eye sees them; however, the eye guesses them in the Orient. This means that the Oriental cannot envision that a floor rug can be made with genuine flower figures. He hesitates to step on him with the thought that it breaks and withers; On the other hand, he cannot imagine that animals can be stepped on: Moreover, animals such as lions, tigers, deer stand on the floor carpet with a horizon, which they have no tolerance for. Do not think that this is my personal opinion; Many Orientals’s I have been expressing what I heard from the mouth “( Art in Turkey and crafts are , p. 106). “… It is understood that it does not take the shape of Oriental objects, but the idea of a shape, that is, a decorative possibility” ( ibid . , P. 116). It is certain that the motifs have a meaning. For example, the “tree of life”, which is also used in Anatolian rugs, represents heaven. The source of water, trees, plants, and sometimes the animals that roam among them , mostly seen in Persian carpets, reflect the love or longing for nature. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the pattern that gives the carpet its name in Anatolian “birdli” carpets is not actually a bird, but a deceptive shape created by filling the ground in the middle of two opposite leaves from rosettes lined up on the same axes (Yetkin, p. 106-113). The “crow embroidered” carpet mentioned in the narh book dated 1640 is probably the same type of carpet (Kütükoğlu, p. 72). Animal figures XIV. Century, it has become stylized and has an ornamental character and entered Anatolian carpets. These are often placed as fillings in geometric motifs. The first animal and bird figured carpets were found in XIV in the paintings of European painters. Since it emerged in the 19th century ( as.bk. ), the origins of such motifs should date back to a century ago. Among the animal figures, there are also mythological ones.

Major carpet weaving centers have applied unique motifs. Therefore, the motif of the carpet also points to the place where it was made. For example, a Yağcıbedir carpet usually includes mercury , comb, hooked, bird, flower in a pot, belly motifs and chicken feet, centipede , female lips, anchor star, gongolak , bayonet, ram horn, and crowding motifs. The motifs of the carpets generally reflect a culture. For example, the motifs carved into the stone adorning a crown door on the Selçuk carpet are exactly repeated on the carpet. Usually the motifs seen in the carpet tile making, bookbinding and architectural motifs used in a great similarity exhibits . Motifs sometimes reflect a belief, and holy places longed for are depicted, especially on tapestries. The depictions of dragons and emeralds on some carpets probably reflect a belief from the totemism period.

Carpets have a wide range of uses and they are also named accordingly. Rugs laid on the ground as a floor cover usually consist of four pieces. The one placed in the middle of the room is called the “middle carpet” ( meyâne ), the one placed on both sides is called the “edge carpet” ( kenâre ), and the one placed on the side of the sofa in front of the windows is called the “main carpet” ( serendaz ); four of them are called “decks”. The largest carpets are called “floor carpets”. Carpets are also used for covering cedar and corner pillows; Rugs laid on cedars are called “cushion carpets”. In Turkish and Iranian cultures, saddlebags are often woven with carpet technique and symbolize the nobility, wealth and taste of an elegantly patterned saddlebag rider; In this respect, saddlebag has an important place among nomads. The storage of clothes, underwear or precious items, which the nomads call coarse sacks, are usually woven with the carpet technique.

Generally, the mountainous region of Asia with high plateaus located between 30-45 degrees north latitude is called the “carpet belt”; In the south of this zone, it is common to use straw due to heat, and post due to cold in the north. Scientists such as Uhlemann and Kurt Erdmann said that the homeland of the carpet was the steppe region extending from the western end of Turkistan to the border with Mongolia due to the geographical conditions. The oldest knotted carpet example that has survived is the carpet, which was found by Russian archaeologist SI Rudenko in a kurgan in Pazırık between 1947-1949 and is still preserved in the Hermitage Museum. 1.89 × 2 m. The carpet has reached our time without much deterioration due to frost and has created a very important document in this regard. Before death V-IV. This rug dating back to centuries and containing thirty-six Turkish-style knots per square centimeter is thought to be a saddle cover despite its size. The carpet has five borders, two of which are wide and three narrow, and the floor is divided into squares equally like a checkerboard. Inside the squares is a star-shaped flower motif with four leaves, while on the borders there are depictions of a lion- griffin , a cavalry and a shelter (Central Asian deer) on a horse whose tail is tied and whose mane is cut. Cross flower and leaf motifs are a great resemblance to the widespread ornaments still used by Turkmens on floor rugs, saddlebags and sacks (for examples, see Kırzıoğlu , p. 28-37), especially the cavalry and shelter figures on the Scythian artifacts found in West Turkistan. presents . Sir Marc Aurel Stein , 1906-1908 years between the East in the excavations carried out in Turkestan in Lou-LAN, a pit with Lop- the nori is a Buddha found that knotted carpet pieces in the temple Pazirik is a little more recent than the carpet ( BC . III century). These pieces, which are preserved in the British Museum and New Delhi Museum, attract attention with diamond, ribbon and stylized flower motifs and three kinds of yellow, dark blue, red, brown and dull green colors. In 1913, A. von Le Coq , during his researches in the Turfan region of East Turkistan , found the oldest in a temple III after AD and the newest VI. He found various carpet pieces belonging to the century. As far as the regions where these oldest examples were captured can be determined , VI. Considering that the knotted carpets were completely inhabited by Turkish tribes since the 19th century, it is necessary to admit that the knotted carpets were first touched by the Turks (Huns). The development of knotted carpets, which is essentially a technical invention, arose from a need for the lifestyle of the members of the equestrian steppe culture. All of the tent furnishings consist of carpets, felt covers and various mats, and these carpets, which cover everywhere according to the material power of the tent owners, constitute the main comfort and decoration of the steppe life.

When the Turks passed to the settled civilization, they often preserved their old life styles. Carpet is one of the most important necessities of tents and fixed houses. While describing the house of Salur Kazan in the Book of Dede Korkut , the expressions “Ala kalî were furnished in ninety places ” (Ergin, p. 95) and while talking about tent furnishing, “Ala kalî furnished ” ( ae . , P. 188) are mentioned. In this respect, carpets were definitely produced in the first cities where Turks lived. VII from Chinese sources. It is learned that carpets were woven in Hotan in the century ( Grousset , p.148 ). Bukhara ruler Tuğ- Sadak, 719 were located in the carpet between the gifts sent to the Chinese ruler (Sumerian, pp . 32 [1984], p. 45). The fact that the carpet was counted among the popular commodities of Bukhara in Ḥudûdü’l-ʿâlem (p. 112) shows that the city preserved its importance in this respect in the following centuries. Author also Transoxanian to the Çâgāniyân connected in Dârzengî is stated that tap carpets and rugs (p. 114).

The Arabs’ acquaintance with the carpet is mostly due to commercial connections. From the expression “dome Turkey ” in some hadiths, it is understood that they know about the Turkish tent (see ÇADIR ) and therefore have more or less information about their culture. In this respect, it is natural for them to know the carpet and to include some words related to it in their language. However, Hz. The word nemat , which is mentioned in a hadith of the Prophet advising newlyweds to keep mats in their homes ( Bukhari , ” Menâḳib “, 25, ” Nikâḥ “, 62; Muslim, ” Libâs “, 39-40) it should be interpreted as a fine weave such as a mat or rug, not a carpet. Muslims had the opportunity to get to know the carpet closely during the conquest of Iran. Hz. Among the spoils seized by the capture of Medâin during the Omar period , there was the famous carpet called ” bahâr -ı Hüsrev” that the Arabs bought from the palace . The embroidery of the carpet, which is said to be woven from silk and adorned with gold, silver and precious stones , reflected the spring, as the name suggests ( Pope , VI, 2274-2275). Due to its size, it was not deemed appropriate for such wealth to go to a person, and the carpet was disintegrated and distributed among the veterans. Even after the conquest of regions such as Azerbaijan, Iran and Central Asia in the “carpet belt”, the Arabs did not give up their straw and felt traditions immediately. However, after a while, the carpet started to occupy an important place in palaces and mansions as a sign of nobility . Especially during the Abbasid period, the need of the palace was met with carpets woven in houses and considered among taxes. It is rumored that the carpets sent to Hârûnürreşîd (786-809) from Horasan occupied 200 rooms. Memun of (813-833) 600 between the tax Taberistan is said to be the carpet. The Abbasid caliphs sometimes covered the floors of their palaces with mat and the walls with carpets ( ibid . , VI, 2276, 2277). However, the public was not yet able to understand its value and embrace it. Hârûnürreşîd the first degree rising singer Isaac Bersûmâ’y to as a gift, to Cahiz’in carpet itself based on 2000 dinars worth it when mom greeting knives from the pieces cut in deploying illustrates this. When Ishak explained the situation to Hârûnürreşîd , the caliph laughed and gave him a new carpet ( et- Tâc fî aḫlâḳl-mulûk , p.41 ). The value of 2000 dinars determined by Câhiz suggests that this carpet was decorated with silk and maybe precious stones. Some Abbasi carpet fragments belonging to the Sâmerra period (836-892) have survived to the present day ( DİA , I, 35). Lamm by in Fustat found that parts of Central Asia show a great similarity to Turkish carpets and scientists in the Fustat the issues they brought from Iraq or they touch Do debate is to (see for detailed information. Ibid . , II, 56). It is certain that the Turks , who were assigned to the state for military purposes since the Umayyad period, played a major role in the introduction of the carpet to the Islamic world during the Abbasid period .

During the Seljuk period, the carpet spread throughout the Islamic world; Some cities and towns of Anatolia in particular gained fame in this regard. The first information about Turkish carpet weaving in Anatolia is given by the geographer Ibn Saîd el-Maghribî (d. 685/1286). While the Maghribî Kitâbü Basṭi’l-arż fi’ṭ-ṭûl ve’l-ʿarż describes Anatolia in his work, “Turkmens are a large tribe of Turkish descent and conquered the Greek country during the Seljuk period. They flock to the shores frequently, selling their captive children to merchants. It is these Turkmens who weave Turkmen carpets (el- büsûtü’t – Türkmâniyye ) . These carpets are sold to all countries ”(p. 117-118) and mentions the beautiful wool carpets of this area on the occasion of Aksaray (p. 119). Ibn Battuta in Aksaray is characterized as one of the most beautiful and spectacular cities in Anatolia and said: “the town with respect to the sheep that produced the wool be permanently there is no place in a taunting. These are sent to Damascus, Egypt, Iraq, Hind , Sîn and bilad -i etrâke ”( Seyahatnâme , I, 324). As a result of the negative attitude of the communist Chinese regime against the ancient cultural remains in Tibet, the monks could not show the old meticulousness in the preservation of the historical objects in the temples and some carpets known as the “Tibetan group” because they were brought from here, travels , especially Ibn Battûta, from Anatolia to the East. confirms the information given by the carpet as it was exported. Technical analysis XII-XIII. These carpets, which are shown to belong to the centuries, have characteristics unique to early period Turkish carpets. Animal compositions, highly stylized human faces and other motifs as well as color, raw material and weaving technique show that they are of Anatolian origin. These finds unexpectedly enriched the group of carpets with animal motifs in the early period, known as the oldest Anatolian carpets until now, and the XIII. An example with the Konya carpet group dating back to the 19th century was purchased by Bode in 1890 for the Berlin Museum , and an example was found in the church of the village of Marby in Sweden . He added a link to the chain between Anatolian carpets with geometrical and animal motifs ( a.bk. ) (Meter, Turkish Carpets , p. XI).

The oldest carpet samples, after those found in Central Asia and Fustat , were discovered in Konya Alaeddin by FR Martin in 1905 and in Beyşehir Eşrefoğlu mosques in 1930 by RM Riefstahl . century Anatolian Seljuk carpets. One of these examples, most of which are large, is 2.85 × 5.50 m. It exceeds 15 square meters in size. In a copy of Maḳāmât registered in Istanbul Süleymaniye Library (Esad Efendi, nr . 2916), again, XIII. There is a Seljuk carpet depiction of the century. Seljuk rugs are generally woven with a slightly inclined Gördes knot from right to left or left to right. The motifs are mostly of geometric character such as diamond, eight-pointed star and octagon with hooks; Sometimes suitable plant motifs are used. The floor compositions of carpets are generally made up of these simple shapes that are arranged one on top of the other and side by side. The most distinctive feature of Konya Seljuk rugs is the large kufi writing decoration on their borders. An irregularity is observed in the corner transitions of the vertical kufi letters, which are terminated with sharp triangles resembling an arrowhead at the beginning. This style was later used in the form of a braided and flowered kufi border from Caucasia to Andalusia. Beyşehir carpets also have the technical and pattern features of Konya carpets.

Carpet weaving maintained its importance in Anatolia during the period of principalities. Valuable carpets were woven in the tribe of Osman Bey, the founder of the Ottoman Empire, which took its place at the western end of Central Anatolia . According to Âşıkpaşazâde , when Osman Bey returned from the plateau, he would present cheese, carpets, rugs and lambs to the Bilecik tekfur, and when he was invited to a wedding, carpets were among the gifts he took; The carpets and rugs he gave to Köse Mihal at her wedding were very much appreciated ( Âşıkpaşaoğlu Tarihi , p. 9, 18-19). Maras Elbistan living in the area, then holding referred to in this place of residence of the present Yozgat Bozok name motive which Dulkadirogullari in mAktAydIlAr carpet fabric (sumer, pp . 32 [1984], pp. 48-49). Karamanoğlu Alaeddin Bey congratulated Murad I for his success in the Balkans and sent him some gifts in a letter. Among these gifts were four big and five small “double kalî -i Karamanî ” (Feridun Bey, I, 103). However, Feridun Bey does not give any information about the city of the principality where these carpets were woven. Marco Polo also praises the carpets woven in Anatolia and points to Konya, Sivas and Kayseri as the main centers.

Clavijo , while describing Timur’s tent in his travel book , states that the throne and cedars with three or four layers of mattresses on which the ruler sits, and that the floor was covered with silk carpets when talking about another tent ( Travel from Kadis to Samarkand in the Timurian Period , II, 48, 68). XIV. The carpet depictions that appeared in century Iranian miniatures increase in the Herat school studies under the patronage of Timur’s grandson Baysungur . These miniature, as common in the western painters statements referred to in their name ( aş.bk .) Specimens of a number of small patterned carpet -meselâ Holbein – it is possible to see. This period nâme is one of the carpet pieces Athens Benaki in the museum and the background pattern are copied embodiment for as baysungur humanized vi Humayun ‘s Vienna in Nationalbibliothek the copies, with ( v . 10 b ) in the miniature resembles carpet ( Lentz-Lowry , p. 220 ). Especially XV. century Herat Kufi border of the carpets depicted in miniature school, Holbein and Lotto with carpet Bellini doge from Loera a great similarity to the border of the carpet in the table exhibit .

- One of the rare examples of century Turkish carpet art is the ” Marby carpet” . On the carpet, the floor is divided in half, and two birds standing on either side of a tree are placed in octagons in each partition. A similar rug found in the Stockholm Museum is in Konya Mevlana Museum, and a similar one is in the Carpet and Kilim Museum. The surface of this last carpet, which was recently unearthed in the Foundations carpet warehouse in the Yenicami Hünkar Kasrı , was divided into two as in the Marby carpet, two dragons standing on both sides of a tree in two flattened rectangles and four stylized emeraldhanka figures placed symmetrically on the lower and upper corners of these. . Museum in Berlin Bode in the carpet (part) ejder- zümrüdüanka place was given to the fight.

- One of the important carpet weaving regions in the century is Egypt. Carpets found in Fatimid palaces that changed color like a chameleon with the arrival of the light were called ” pencils ” because of these features . Carpet weaving in Egypt, XV. It has shown a great development in the Mamluk period starting from the middle of the century . In the Mamluk carpets , where extremely soft “S” twisted woolen threads and pastel shades of red, green, blue and rarely yellow are used, the main scheme is made up of medallions intertwined with geometric motifs such as concentric triangle, rectangle, octagon and star. Cypress motifs are sometimes added to the decorations found on these carpets . Although they are usually woven in a medium size and square shape, there are also longer than normal medallions that are repeated in proportion to the length of the carpet; Large samples have hardly survived to this day. The European official also often seen in the Mamluk carpet for West resources base ” Damascus (Damascus) carpet” has used the term. These carpets, which have unusual dimensions, are definitely considered to be woven to order.

XVI. It is the period when the most beautiful examples of the carpet art of the century in the triangle of Iran, Egypt and Anatolia began to be given. The most important centers of Iranian carpet weaving in this century are Isfahan, Kashan , Tabriz, Kirman, Herat , Shiraz , Hamadan , Yazd and Karabakh in Azerbaijan. The oldest known example of the Safavid carpet, which showed a great development especially in terms of motifs in this period, is the carpet, which is found in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan and dated to 929 (1523) by the signature of Gıyâseddin Câmî . Again, one of the oldest examples is in the Victoria and Albert Museum today and is 11.51 × 5.34 m. is in size. This carpet, which is understood to have been woven in 946 (1539) from the expression on its edge and was previously laid in the tomb of Sheikh Safiyyuddin in Ardebil, the ancestor of the Safavid dynasty , is considered an important work of art. There are many different examples of Persian rugs displaying finely embroidered symbolic flowers, garden-style schemes and geometric shapes. In particular, there are animal figures on the borders and floors of the carpets with painting patterns, many of which resemble a page with miniatures, and the fight between animals with this type of hunting scenes takes an important place. Similar motifs are also found in Bâbülü carpets, which are seen to be very advanced in the same century . It is known that Babur’s grandson Akbar placed carpet masters in cities such as Agra , Fetihpûr and Lahore and turned them into carpet weaving centers ( Ebü’l-Fazl el- Allâmî , I, 57). Herat carpets have a significant effect on these carpets. It is seen that such a rug preserved in the Fine Arts Museum in Boston resembles a book page with miniature like Safavid carpets.

XVI-XVIII. Centuries constitute the heyday of Ottoman carpet weaving. During this period, Uşak, Bergama, Kula, Gördes, Konya, Niğde, Kırşehir, Sivas and Kayseri were the most important carpet weaving centers of Anatolia. It is said that in 1514, Yavuz Sultan Selim returned from Tabriz, famous for its carpet weaving, to Istanbul with around 1000 artists in different professions; There were probably carpet masters among them. Câhiz Kitâbü’t-Tebaṣṣur fi’t-ticâre (p. 34) introduces the Azerbaijan-Armenia region, including Tabriz, as a place where felt and fine carpets are brought. After the conquest of Egypt (1517), it is seen that weaving wool dyed by carpet masters was requested from here. It is certain that carpet weaving in the Mamluks, as in every branch of art, has some unique features, especially in terms of motifs, and the Ottomans undoubtedly benefited from this. Again XVI. Towards the end of the century, ten carpet masters, whose names were given by a decree written to the beylerbey of Egypt, and thirty weigher colored ropes were requested (Kütükoğlu, p.70). It is known that later , Mamluk style carpets with arabesque motifs were woven in Anatolia and they were called Egyptian carpets.

Among the Ottoman palace people, the ones who weaved carpets ( cemâat -i kalîçebâfân ) were also counted among the craftsmen known as ” ehl -i hiref ” . The names of six kalîçebâfans and their ten poets are found in a book of Ahl- i Hiref dated 932 (January 1526) . Hamza Kethüdâ, who received the highest wage among them (15.5 coins) , came as a “ claw ” during the reign of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror . In addition , a brief information is given about Mustafa, the father of Mehmed , one of the poets , ” He was one of the master masters of Sultan Mehmed Han and became a slave of the aforementioned Sultan Bayezid Han ” ( Uzunçarşılı , XI / 15 [1986], pp. 57-58). ). II. Bayezid timely congregation -the Ahl -of Hiref in the kalîçebâf number of them were up to nine and Speed, Elijah Alexander, Ismailia and NASUH names which in return whether carpet gift to the sultan of ‘ am and bestowed a nail had been (Çetintürk, p. 722). During the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent , the number of fine carpet craftsmen was about 25 and most of them had figures showing that they came from the European side Ottoman lands such as Wallachia, Niğbolu, Kosovo, Bosnia and Croatia ; some of them are Circassian ( ibid . , p. 723).

Palace rugs, XVI. They are carpets with extremely intricate patterns woven using the cine knot technique since the 19th century and using pastel colors. Although these rugs look similar to Persian rugs, they have a different character. The medallion, which stands out due to the small and dense main floor motifs in the Iranian samples, became an element of decoration in the background of the Ottoman palace carpets, whereas the large motifs of the main floor came to the fore as the main decoration element. Another feature is that it contains tulip, hyacinth, carnation, spring branch and rose motifs, as well as dagger leaves and rumi , woven in a naturalistic way . One type of carpets produced in the palace during this period is the inscribed prayer rugs. A prayer rug gifted by Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent to Mawlana’s tomb gives enough information about them. Woven with fine wool yarn 180 × 116 cm. This prayer at the altar in size, belt padding and border on a red background with yellow, green, lapis lazuli Rumi , error patterns, curved branches and with rosette is decorated. Under the altar arch with stylized Chinese clouds and flower motifs on three dark blue medallions, there is an inscription ” Allahuekber ” written in black thuluth on a white background . In addition, the upper side of the wide border into three lines of Isra sura of the “dark night of the return of the sun until bastırınca make upfront vakitlerde- prayer; Also, perform the morning prayer ; because this is the witness of the morning prayer ” in battles; 78 verses are written. These types of prayer rugs, whose motifs were probably drawn by palace artists and used in palace and pasha mansions, constitute a separate group in the Ottoman period carpet art under the name of “inscribed palace rugs”. The difference of these from Anatolian prayer rugs is that their altars are not gradually arched, but with soft lines in the silhouette of a human head and shoulders, and verses are written on the upper borders . The first examples are XVI. These prayer rugs seen in the 19th century were also presented to mosques and masjids and laid on the altar. XIX. There are also beautiful examples of this type among the prayer rugs, which were woven by the masters who came from Sivas and settled in Istanbul Kumkapı with the Hereke silk prayer rugs belonging to the end of the century .

Carpet XIII recognized in Europe during the Crusades. It spread as a luxury consumer item at the end of the century, and palaces and castles began to be furnished with carpets. Carpet imports from the East show a great increase in these years. Especially the carpets brought by the Italian merchants were almost fought by the rich. The people who posed for the famous painters of the period accepted these carpets as an element of prestige due to their high cost and wanted them to be included in the décor of their paintings. In compositions of religious nature, especially in the paintings of prominent figures of the period, it is seen that a Turkish carpet is lying on a table or on the floor, or hanging from a balcony or adorning the apse of a church. Usually stylized birds, roosters, single and double-headed eagles or four-legged animal figures fighting with each other are known as “animal carpets”. century, it has been determined by looking at the paintings of Western painters ( Erdmann , 52-56). XV. From the 1st century onwards, carpets with animal figures in the paintings were gradually replaced by geometric and floral motifs that were stylized incomprehensibly to the original geometric shapes, especially octagonal and lozenge compositions lined up on different axes . These rugs, known as ” Holbein carpets”, are mainly divided into four types, as they are mostly seen in the paintings of the German painter Hans Holbein (d. 1543) . In the first type of Holbein carpets, also called “small sample”, the floor is divided into small squares, and an octagon is placed inside the squares, contoured with a knotted strip . The big lozenges, which are formed by combining the quarter lozenges at the corner of each square, form the main scheme. The octagons have a small octagon with an octal star filling in the middle. Thus, a row of diamonds and a row of octagons appear on different axes. The color of the floor in this type of carpet is usually dark blue or red; There is also a small amount of green. The border is a pseudo-writing belt in kufi character that has become a knitting motif. In Piero della Francesca ‘s 1451 mural in the Rimini San Francesco Church , the carpet on which the prince kneels in front of Saint Sigismond is the first example of this type seen in European paintings, which was later continued by many painters for more than a century. One of the latest examples is seen in a painting of an unknown artist, dated 1604, ” The Somerset House Conference,” exhibited in the National Gallery of London ; The carpet covering the long table is depicted very vividly with its kufi border. The carpet in the painting is in XVI. It bears almost the same motifs as a piece of carpet from the early century.

The second type of Holbein carpets, also known as ” Lotto carpets” because they are seen several times in the paintings of the Venetian painter Lorenzo Lotto (d. 1556), seem very different from the first, but in fact preserve the same scheme. The octagons and four armed lozenges whose contours disappear completely lost their first type of geometric character. Most of these carpets, which are seen to be dominated by plant motifs, have yellow rumi palmette composition on red background and sometimes on dark blue . In addition to the borders developed from Kufi, rich and different borders with cloud motifs, cartridges and curved branches, reminiscent of classical Uşak carpets, also attract attention. It is understood from the samples bearing the coats of arms of some families that these carpets were also made to order. This type of carpets XVI. Starting from the century XVII. It took place in the paintings until the second half of the century.

The third type of Holbein rugs shows a plain example where several large squares filled with octagons are placed side by side, placed wide on the floor, and for this reason it is also known as the “large sample Holbein carpet”. XV. The roots of this type of carpets, which developed throughout the century, are based on animal carpets and carpets with geometric motifs, which can also be seen in the paintings of the previous century. The squares are equal and surrounded by a frame of geometric or floral motifs. The knitted kufi borders seen in the first examples are characteristic. In Europe from Holbein recognized before 1560 and up to the Italian, Spanish, French and British painters such statements carpet pattern seen in the first two examples and details with respect to more wealth exhibits . A good example of this type of carpets can be seen in the painting “Saint Giles’s Devotion “, exhibited in the National Gallery of London and whose painter is unknown , and there are also very fine examples of this type of carpet in the Istanbul Turkish and Islamic Works Museum and the Carpet and Rug Museum.

The fourth type of Holbein rugs is an advanced and different form of the third type. In this type, it is seen that a composition consisting of two small octagons on both sides of a large square filled with octagon in the middle is a great innovation. At first glance, it may be thought that this genre has Mamluk influence, but two examples in the Istanbul Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art clearly show that it developed in connection with the third type. Of these, especially XVI. The one dated to the beginning of the century clearly reveals the connection between these two types by placing two large squares on top of each other and having two small octagons next to them. The knitted kufi border also shows the Turkish character of the carpet.

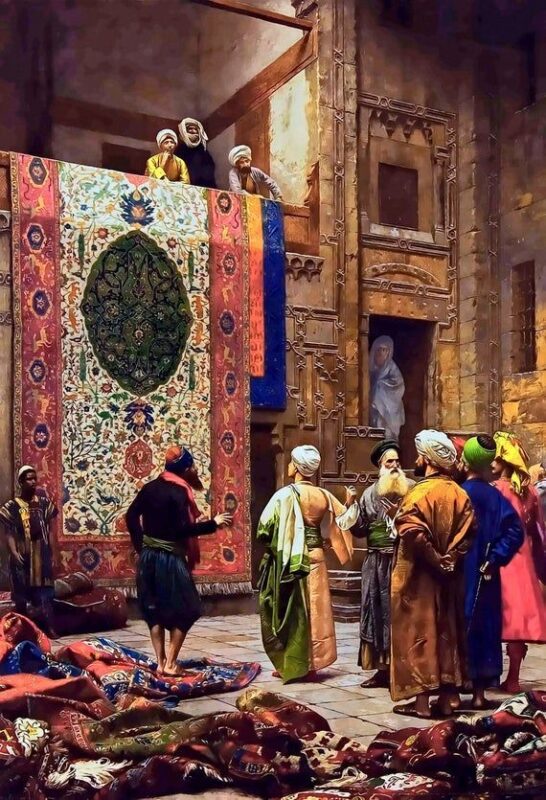

Bellini carpets are one of the carpets named after the western painters. These are also called “keyhole rugs” because the altar niche expands downwards to form a keyhole image. XV and XVI. These carpets, which were widespread in the centuries and included in the paintings of painters such as Lorenzo Lotto , Vittore Carpaccio , Benvenuto Tisi, Jacopo Bassano , and Mansueti , were known as “Bellini carpets” because they were widely used by the Italian painter Giovanni Bellini (d. 1516). A group of Anatolian carpets linked to the examples described above but bearing different motifs are also named after them, as they appear in the paintings of Italian painter Carlo Crivelli and Dutch painter Hans Memling . XX. century came in Giulio Rosati , Rudolf Weiss , Giuseppe Signorini , Rudolf Ernst , Charles Wilde , Arthur Melville , Benjamin- Constantine , Charles Robertson , Jan- Baptist Huysmans and Osman Hamdi sugar with Mr. Ahmed who Pasha and Halil Pasha teacher Jean Leon One of the most important subjects of Orientalist painters like Gérôme was carpet sellers, and in some cases, carpet sellers. Osman Hamdi Bey also included a lot of carpet in his paintings; is also the subject of a painting he made in 1888, which is still in the Staaliche Museen zu Berlin National Galerie (AI 420), and is the carpet seller. One of Rudolf Swoboda’s paintings is XX. It is about carpet repairers, a profession in the early century ( Thornton , p. 193).

XVII. It is understood that some towns of Anatolia gained a great reputation in carpet weaving in the century. While mentioning the prayer rugs sold in the Ottoman market in the middle of this century in the narh book belonging to 1640, ” Germiyan Kulası’s Egyptian embroidered”, “Malik Pasha style”, ” Germiyan Kulası with a post”, “Selendi’s peleng embroidered”, “Egypt’s seven altars. When talking about prayer rugs and carpets, “Uşak’s kalîçe on red “, “the center of the table-shaped kalîçe “; “Selendi’s hammam castle with crow embroidery on white ”; Expressions such as ” Gördüs yellow crushed hammam kalîçe ” were used, and the prices were given between 400 coins and 5500 coins, depending on their quality and size. From this information, it is possible to draw some conclusions about the places where prayer rugs and carpets are woven, their motifs and values (Kütükoğlu, p. 177-179). The main carpets named according to the centers that became famous in this period are as follows:

Uşak Rugs. The second and the most brilliant period of Turkish carpet weaving after the Seljuk carpets is XVI. It starts with carpets woven in Uşak and its surroundings in the 16th century. Despite its great reputation, Uşak rugs, which are usually only named as Turkish carpets in the inventory records, are classified in two main groups: medallion and star. Medallion carpet depictions XV. century Herat school miniatures; such Ordinance -U Gencevî’n the Hamsa of them from 849 (1445-46) dated a copy ( v . 62 a ) is one common example of which ( Lentz-Lowry , p. 108). In this type of rugs, the medallion sequences that stretch forever on the shifted axis and the rumi , curved branch and flower motifs between them sometimes take on a naturalistic character. XVI and XVII. The fact that Uşak carpets with medallions are found in the western painting of the century shows that they were exported to Europe since the date of production, and an example in the Berlin Museum bearing the coat of arms of the Polish Wiesiolowski family shows that they were also made to order. The star group resembles the Uşak medallion carpets in terms of its general composition and mostly in its late samples. In the early examples, it is seen that the half and quarter lozenge shaped small medallions in the extension with an eight-pointed star in the center are alternately lined up on the shifted axes, and the pale floor fillings with vegetation patterns form a composition reminiscent of Holbein carpets by making a second order . Ardabil motifs on these carpets (Iran) said if the influence of the stars, especially Garagoyunlu work in Tabriz Gökmescid the tiles with those in the exhibit is remarkable similarities.

Usak carpets are generally dominated by red on the floor, medallions and stars in dark blue. A species with a white background is referred to as a “carpet with a bird” because its pointed leaf motifs remind of a bird figure. In all types, individual blue, green and yellow form mostly fine motifs. Çintemani , one of the most popular motifs , is repeatedly filled on the floor inside the border within the principle of infinity, and is sometimes used as a floor filling in medallion types . There are several other varieties of Uşak rugs such as Chinese clouded lozenge pattern, Chinese cloudy medallion and flower-filled floor. In addition to these, a group of Uşak rugs with a border decorated with double altar cartridges on the edge and floral and stylized crab motifs on the floor are also called ” Transylvanian carpets”. In fact, this term comes from the Hungarian churches in the Transylvania region to the Turkish carpets exhibition held in Budapest in 1914, and a large part of the XVII. It is a name given to more than 200 rugs consisting of single and double altar prayer rugs from the century and beyond ; it became widespread later.

Gördes Rugs. Gördes , a town in Manisa, established next to the old Gordos in the upper part of the Gördes stream , has a very important place in Turkish carpet weaving and for this reason, the Turkish knot is referred to here . Carpet weaving in Gördes, especially XVII. century had its most brilliant period; The carpets woven in this period are mostly prayer rugs. Gördes prayer rugs are dominated by different shades of red, brown, blue, dark blue, green and white; Carpets with dark blue floors are considered more valuable. XVII. Century rugs take the names “Gördes with a girl, Gördes with a navel, Gördes with a mihrab, Gördes with a lamp, Gördes with a marpuç, pure Gördes” according to their designs. The rugs called Kız Gördes, as they are woven by young girls as a dowry, are usually double altar and have white floors; There is a small belly in the middle and the edges are decorated in a zigzag shape. Göbekli Gördes rugs also have double altars ; There is a small belly surrounded by flowers on the floor and it is decorated with pitcher motifs. Kandilli Gördes rugs have a single altar . In the middle of the altar, an oil lamp or a bunch of flowers hangs on the carpet floor; sometimes there is a flower bouquet under the oil lamp. The samples without lamps are called ” mihrab ” and those with columnar sides of the mihrab are called “gordes with marpuçlu”. XVII. In the century, carpets where more than one person can pray side by side were also woven; These carpets, which are called “pure prayer rugs” today, have many altars adjacent to each other. In Gördes, which continued its tradition with some minor changes in the next century, the XIX. Century , bespoke carpet weaving for the Oriental Carpet Manufacture company. Chemical dyes replace vegetable dyes. Some differences in patterns occur, and in the late examples, the mihrab and the pillars next to it take on an architectural shape; In addition, borders and arches are decorated with plant motifs with thin branches and leaves. There are also carpets with tughra and starboard depictions on the floor. These carpets, which emerged during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid, were called ” Mecid Gördes” among the public , and “baroque” or “red Gördes” in foreign sources. In the past, there was a loom in every house in Gördes and its villages. Today, outside the center, Değer, Tubular, Kalemoğlu , Alanyolu , Doğanpınar , Güneşli, Painted, Çiğiller, Bayat, Balıklı, Tepeköy and Karayağcı villages continue the tradition.

Kula Rugs. Like Gördes, Kula is a district of Manisa. XIX. Until the end of the century, his rugs came third in Western Anatolia, after those of Uşak and Gördes. Kula prayer rugs are similar to Gördes’s prayer rugs due to their closeness; but their colors are more matte. Apricot and golden yellow, red, blue, white and rarely green were used. The borders are in the form of elaborately processed thin strips. The mihrab floor is filled with motifs such as house, cypress or any tree, tombstone. The most characteristic Kula prayer rugs are XVII and XVIII. made in the century; In the next century, quality began to decline and patterns began to deteriorate.

Milas Rugs. Milas is a district center of Muğla province. Carpet making in the region XVI. century since the XVII in Milas. It started to develop at the end of the century and continued for two centuries. Peach red, honey color, yellow and white colors are characteristic. Milas prayer rugs usually have three wide, nested borders in the middle. The outer thin water is decorated with triangles called notches and small floral motifs. The floor of the same width as the curbs is broken with dashed lines to form a rhombus. There is a realm or tree of life motif on the mihrab, small stylized flowers and leaves on the edges, and geometric fillings on the ground. The pediment is decorated with stylized flowers. There are different types of Milas carpets named according to their motifs such as Karacahisar navel, scalloped, rattles , and serpentines.

Konya Region Carpets. Konya region, whose reputation in carpet weaving began in the Seljuk period, includes Karapınar, Sille, Obruk, İnlice village, Lâdik, Sarayönü, Ereğli and Karaman. In the diagrams of the regional rugs, the geometric parts of the lozenge, knot and octagonal stars connect to each other. Bi-directional cleats inside of the hook with an octagonal diamond and impregnated . Occasionally hooked and stepped octagons form the ground sample. Prayer rugs can be single and double altars . Among the ladik carpets, especially XVIII. The ones dating to the 19th century are in prayer rug style. In these, the ground is usually red, and the borders are brown, blue and white. There are usually two borders around, one narrow and the other wide; The millet is adorned with surprising small flowers, while the large one is decorated with floral motifs called “ball tulip” or “Ladik rose”. The floor of the mihrab, narrowing in the form of a stair step, is sometimes left empty, sometimes decorated with a tree of life motif; In some examples, the writing is seen. Below or above the mihrab are five or six plant motifs called hyacinth, linden and poppy; which is sütunçel there are also ones. Of the ladik carpets, XVIII-XIX. Its steady development over the centuries affected centers such as Karaman, Karapınar, Aksaray and Kırşehir, leading to the spread of the Ladik carpet model to the entire Konya plain and to the emergence of species such as Karapınar Lâğı and İnlice Lâği after a while . For this reason, in foreign sources, it has become a fashion to call every carpet produced around Konya without showing a center. Although some centers such as Karaman, Karapınar and İnlice still produce Ladik type prayer rugs, there are deviations from the old tradition such as the use of synthetic dyes, cine knot application and Isparta type production.

In the early 1860s, carpet weaving in Western Anatolia was under the control of a few merchants who supplied the villagers with materials and made them work on order. Their early work from home gives a near Haji Ali Effendi year 3000 and 84,000 m 2 was due dokutuy carpet. The first signs of British capital infiltrating carpet weaving were seen in 1864. Three British merchants started to export the carpets they had made by giving yarn and model to some carpet weavers around Uşak. Advancing slowly and steadily, the British had monopolized carpet weaving in Western Anatolia by the mid-1880s . Six large commercial organizations, headquartered in Izmir, had taken over the entire production process from spinning carpet yarns to export ( Dölen , p.353 ). Extremely cheap labor to provide large profits the British with this effort in 1884 to 155,000 m 2 of carpet production rose to 367 876 square meters in nine years the region. In the same years, İzmir’s carpet export amount increased from 3 million francs to 7.5 million francs . Since the British made sweet profits by employing home business in the region, they did not establish a factory (collective manufacturing workshop) in the region, although they held the monopoly of carpet manufacturing and export for nearly thirty years. An Austrian company, wishing to take advantage of their cessation of production, established the first factory in the region and weaved an average of 12,000 m 2 of carpets per year for about eighty workers it started operating . The Austrians’ initial high profits led to the emergence of fifteen carpet companies within a year. However, since these companies could not establish a production and distribution network like the British and had to buy yarn from their spinning and dyeing mills, their production cost 50% more. Realizing that their monopoly situation was shaken and that they would collapse if the necessary measures were not taken, six British merchants founded the Oriental Carpet Manufactures company with a capital of 400,000 pounds . The company, which started with yarn factories, opened seventeen carpet weaving workshops in various regions until 1913 and took the second place after the railway company because it employed workers very cheaply. According to the reports of the board of directors of this company, between 1910 and 1914, 60,082 people were making a living with carpet weaving in 19,145 looms in regions such as Uşak, Isparta, Kayseri-Bünyan together with their surroundings ( Dölen , p.350 ).

In the Feshâne , which was established in Istanbul in 1833 to meet the military’s need for termination, the XIX. Towards the end of the century, carpet was also started to be woven and production continued until 1914. The name Feshâne and the date of manufacture are written on some of the carpets, which are woven especially for the palace and include examples of Iranian and Western imitations, among which are very successful .

In 1891, skilled craftsmen from the carpet weaving centers such as Sivas, Lâdik, Gördes and Kula were brought to the Hereke Weaving Factory , which was founded by two businessmen in 1843 and nationalized two years later, and carpet weaving looms were added. In the beginning, as in Feshâne , wool carpets with arış, weft and loops were woven, and later carpets of fine quality cotton and wool knitted were woven. The Dolmabahçe and Yıldız palaces were furnished with very large carpets woven here, and also silk carpets, silvery prayer rugs and tapestries were manufactured and released to the domestic and foreign markets. The Hereke fabrics sent to the International Textile Products Fair opened in Lyon, France in 1894 and their carpets were awarded a grand prize and a certificate. In the same year, the German Emperor II. When Wilhelm and his wife visited Istanbul at the invitation of Sultan Abdülhamid, they also visited Hereke and this event increased Hereke’s reputation, as a matter of fact, the carpets and curtains of the “Peace Palace” built by the famous businessman Andre Carnegi in La Haye . has been ordered here. Later, a branch of this establishment called Hereke Dokumahânesi was opened in the garden of Dolmabahçe Palace and carpets were woven here until the last days of Vahdeddin.

XIX in Isparta. Although a factory was established here in the first years of the Republic in order to meet the yarn needs of carpet makers who started production at the end of the century, the required efficiency could not be achieved due to the lack of capital. In 1943, Sümerbank took over and expanded the factory and established the Isparta Wool Yarn and Carpet Weaving Organization . In 1976, the Handwoven Carpet Development Project was put into practice and sixteen regional directorates and thirty-six regional directorates were established. In 1982, the factory was developed by purchasing new machines, and in 1987 Sümerbank Holding A.Ş. After the establishment of Sümer Halı, Carpet, Handcraft Industry and Trade Inc. It was named after. In 1989, 3203 people were working in 111 workshops in Demirci, Denizli, Konya, Kula, Sandıklı, Kahramanmaraş, Kayseri and Sivas regions of the Isparta factory. This organization has contributed significantly to the development of carpet weaving in Turkey, both by acting as a principal with the production has been a pioneer in increasing both the quality of the spread of this art.

Turkey’s carpet export, since the Republic’s early years up to 1928 gradually show an increase after 1929, it began to decline and II. During the Second World War, it fell to almost negligible level. Meanwhile, the same decline was seen in carpets imported from Iran, the Caucasus and Central Asia and shipped to the West from Izmir and Istanbul. The most important reason for this decline was the development of machine-made carpet in Europe and America and the countries’ application of protective customs policies. In addition, the economic crisis of 1930 caused quality deterioration in terms of raw materials, patterns, colors and dyeing. After the 1950s, the demand for carpet increased, but cheap and poor quality production became widespread. One of the main reasons the carpet has lost value in the last century is the use of artificial dyes instead of natural dyes in the dyeing of the threads. When washed, the colors that intertwine and the deteriorating motifs reduce the value of the carpet. Recently, in order to prevent this damage and not to waste the efforts given, a project that was initiated for the first time in 1976 within the body of the State Applied Fine Arts School and still carried out by the Faculty of Fine Arts of Marmara University was put forward. Within the framework of the Natural Dye Research and Development (DOBAG) project, a natural dyes research laboratory was established with the support of technical staff of the German government, and further studies for the determination of traditional patterns were started. For the first time, the Karatepe Village Cooperative in Toroslar was helped and it was seen that the rugs produced by adhering to the traditional method had a great market potential. The aim of the project is to revive carpet making in villages with insufficient agricultural income, to help the villagers in weaving new carpets by adhering to traditional patterns and using hand-spun yarns from wool dyed with natural dye, to conduct research and determination studies on this subject , to give warranty certificates to carpets woven for the purpose and can be summarized as playing an active role in marketing. Pilot regions of Çanakkale, Manisa, Bursa, Balıkesir, Bergama, İzmir, Gördes, Uşak and Karatepe were selected for the implementation of the project. Exhibitions, symposiums, publications, conferences were held in countries such as Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium, United Arab Emirates, England, the United States of America, Japan and Norway in order to promote the carpets produced within the framework of the project in foreign markets. A 27 m 2 Natural Dye Research and Development carpet was weaved for a selected carpet maker family for the British Museum in London and placed in the Museum’s Islamic Artifacts Department ( Islamic Gallery) for display ( Dölen , p. 365).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Divan Lugati’t -Turkish , I, 366, 508; III, 164,371-372.

İbnü’l -Esîr, en- Nihâye , ” zrb “, ” ʿabḳr ” md .

Lisânü’l-ʿArab , “ ṭnfs ” md.

JW Redhouse , A Turkish and English Lexicon , Istanbul 1890, p. 825.

Steingass , Dictionary , p. 949.

Clauson , Dictionary , p. 162, 622, 692, 707.

Musnad , VI, 40, 61, 241.

Bukhari “,” Feżâ’il the ASHAB-Nabi “, 6” Menakıb “, 25” wedding “, 62.

Muslim, ” Libas “, 39-40.

Abu Dawud , “ Aḳżıye ”, 21.

Nasâî ”,“ Ḳıble ”, 13.

İmruülkays is v.dğ ., Seven Suspension: al- Mu’allaḳat’s – SEB ( NSR . And TRC . Şerafeddin Yaltka a ), Istanbul 1985, p. 26, 36, 54-55, 68.

Cahiz’in , eth- Taji fî aḫlâḳi’l-Mülûk ( NSR . Ahmed Zeki Pasha), Cairo 1914, p. 41.

a.mlf ., Kitâbü’t-Tebaṣṣur fi’t-ticâre , Cairo 1935, p. 34.

Ḥudûdü’l-ʿâlem ( Minorsky ), p. 112, 114.

Hatîb et- Tebrîzî , Şerḥu’l-Ḳaṣâʾidi’l-ʿaşer , Beirut 1985, p. 56-57, 80-81, 131-133.

Dede Korkut Book ( ed . Muharrem Ergin), Ankara 1958, I, 95, 188.

Yâkūt , Muʿcemü’l-büldân , Beirut 1399/1979, IV, 299.

Ibn Said Al-Maghribi, RECORD Basṭi’l-supply ( , ed . N Gines ) Tıtv of 1958, p. 117-119.

Clavijo , Travel from Kadis to Samarkand in the Timurid Period ( trc . Ömer Rıza Doğrul), Istanbul, ts . (Kanaat Kitabevi), II, 48, 68.

Ibn Battuta , Seyahatname , I, 324.

Aynî, ʿUmdetü’l-ḳārî , Cairo 1972, XIII, 264-265.

Âşıkpaşaoğlu History ( ed . Atsız), İstanbul 1970, p. 9, 18-19.

Feridun Bey, Münşeât , I, 103.

Ebü’l-Fazl al- Allâmî , The Ain -i Akbari ( trc . H. Blochmann ), Delhi 1989, I, 57.

- Dunn , Rugs in Their Native Land , New York 1910, p. 9, 27-29.

- Lesétre , “ Tapis ”, “ Tapisserie ”, DB , V / 2, p. 1995.

Elmalılı, Hak Dini , VIII, 5780.

RC Dentan , “ Carpet ”, IDB , I, 538-539.

Bige Çetintürk, “XVI. Centuries Until The End Hasse carpet that of the artist for ” Turkey San ‘ at the Research and Studies , Istanbul 1963, I, 715-731.

Doerfer , TMEN , III, 396-398, 399-400.

- Grousset , L’empire des steppes , Paris 1969, p. 148.

- Erdmann , Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets , London 1970, p. 52-60.

Oktay Aslanapa – Yusuf Durul, Seljuk Carpets , Istanbul 1973, p. 12-81.

- Haack , Eastern Carpets ( trc . Neriman Girisken), Ankara 1975, p. 27-33, 37.

AU Pope , “ Carpets : The Art of Carpet Making ”, A Survey of Persian Art , Tehran 1977, VI, 2257-2283.

PRJ Ford, Oriental Carpet Design , London 1981, p. 10-40, 42-340.

Esin Atıl , Renaissance of Islam Art of the Mamluks , Washington 1981, p. 223-247.

Mübahat S. Kütükoğlu, Narh Müessesesi in the Ottomans and Narh Book dated 1640 , İstanbul 1983, p. 70, 72, 177-179.

- Thornton , The Orientalists Painter-Travelers 1828-1908 , Paris 1983, p. 193.

Oktay Aslanapa, Turkish Art , Istanbul 1984, p. 342-357.

a.mlf ., Thousand Years of Turkish Carpet Art , Istanbul 1987, p. 9-212.

- Tzareva , Rugs and Carpets From Central Asia , Vienna 1984, p. 6-24.

TW Lentz – GD Lowry , Timur and the Princely Vision , Washington 1989, p. 66, 108, 220-221.

Şerare Yetkin, Turkish Carpet Art , Ankara 1991, p. 36-61, 87-137.

Yeşim Öztürk, Balıkesir-Sındırgı Region Yağcıbedir Carpets , Ankara 1992, p. 16-123.

Emre Dölen , Textile History , Istanbul 1992, p. 348-365, 457-498.

Nazan Olcer, “Carpet Art”, Traditional Turkish Arts , Istanbul 1993, p. 115-135.

a.mlf ., “ Turkish Carpets and Their Collections in Turkey ”, Turkish Carpets from the 13 th -18 th Centuries , Milan, ts ., p. XI.

- Fuat Tekçe, The Story of a Carpet from Pazırık Altay , Ankara 1993, p. 19-21, 32-33, 39, 98-146.

Nejat Diyarbekirli , “Turkish Art Before Islam”, Turkish Art From Its Beginning to Today , Istanbul 1993, p. 15-27.

a.mlf ., “Carpet Weaving in Turks”, Turkish Literature , p . 132, Istanbul 1984, p. 44-49.

a.mlf ., “ Pazırık Carpet”, TDA: Turkish Carpets Special Issue , p . 32 (1984), p. 1-8.

Faruk Sümer, “ The Oldest Historical Records Regarding the History of Turkish Carpet Weaving in Anatolia ”, ae . , sy . 32 (1984), p. 44-51.

Neriman Görgünay Kırzıoğlu , from the Altai Mountains to Tunaboy Common Patterns in the Turkish World , Ankara 1995, p. 1-161.

- Lecomte , Arts in Turkey and crafts are (ready to go. Straight Month), Istanbul, ts . (Tercuman Newspaper), p. 83-119.

Macide Gönül, “Technical Characteristics of Turkish Carpets and Rugs”, Turkish Ethnography Journal , p . 2, Ankara 1957, p. 69-85.

İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı , “ Ehl -i Hıref (Craftsmen) Book in the Ottoman Palace ”, TTK Documents , XI / 15 (1986), p. 25, 57-58.

Bekir Deniz, “Gördes Carpets”, Bilim Birlik Success , p . 45, Istanbul 1986, p. 13-19.

a.mlf ., “ Ladik Carpets”, ae . , sy . 46 (1986), p. 13-18.

a.mlf ., “Milas Carpets”, ae . , sy . 49 (1987), p. 13-20.

Mehmet Önder, “Suleiman the Magnificent Mevlana Tomb Gift ayetli rug”, antiques , pp . 29, Istanbul 1987, p. 13-14.

Önder Küçükerman, “Isparta Carpet”, Antik and Dekor , p . 8, Istanbul 1990, p. 76-81.

Fahrettin Kayıpmaz – Naciye Kayıpmaz , “A Multi-Figured Anatolian Carpet”, ae . , sy . 9 (1990-91), p. 124-125.

Nalan Türkmen, “A Lost Carpet Area Pothole”, ae . , sy . 22 (1993), p. 64-68.

- Ettinghausen , “Halı”, İA , V / 1, p. 129-136.

Mehmed Ali Mehmedoğlu , “Halı (Turkish or Anatolian Carpets)”, ae . , V / 1, p. 136-141.

- Minorsky , “Tabriz”, ae . , XII / 1, p. 89.

- Spuhler , ” Bisāṭ “, EI 2 Suppl . (Eng.), P. 136-144.

- Galvin , “ Bisāṭ (in the Muslim West)”, ae . , s. 144-145.

- Allgrove , “ Bisāṭ ( Tribas Rugs )”, ae . , s. 145-148.

SOURCE : https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/hali–halicilik